How Mongolia can power all of Asia

- Mongolia Weekly

- Dec 6, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 16, 2022

This excerpt is adapted from the book Young Mongols: Forging Democracy in the Wild, Wild East (Penguin Random House Southeast Asia, 2020) by Aubrey Menard with the author’s permission.

The book introduces readers to modern Mongolia through the stories of young leaders fighting to make their country a better, more democratic place.

Much like its cashmere and wool, coal is a resource that Mongolia exports raw without adding value. Frustratingly, not refining its own goods costs Mongolia even more than potential jobs and economic growth—Mongolia is often forced to buy back the refined products of the resource that it sold.

This is the case in Mongolia’s energy sector, where instead of building the power generation infrastructure necessary to turn its own raw coal into sufficient electricity to meet its own needs, Mongolia buys a significant portion of its electricity from its neighbours, Russia and China.

Orchlon Enkhtsetseg (CEO of Clean Energy Asia), who in 2016 made a switch from working in Mongolia’s mining sector to working in its energy sector, says that Mongolia’s reliance on its neighbours for power is a threat to its security and sovereignty. “It’s very hard to call yourself a fully independent country when you have two of your neighbours saying, “If you don’t behave, we’ll turn off the switch,” he says.

Throughout the day, Mongolia is able to meet its own energy demand, but when its citizens return home in the evening, they require additional electricity to illuminate their homes, watch their televisions, and use their appliances. After 6.00 p.m., Mongolia buys extra energy from Russia, using imported electricity to fill up to 13 percent of its needs annually.

Powering the mega mine

Powering the Oyu Tolgoi mining operation has been a major issue of contention between Rio Tinto and the Mongolian government. According to their agreement, the mega Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold mine must operate using a domestic power source by 2022. Building a power station large enough to power the mine will cost an estimated $1.5 billion.

In 2019, the two parties, who were long at odds about where the power station should be located and who should pay for it, finally settled on building a coal-powered plant at the nearby Tavan Tolgoi coal mine. By the agreement reached in June 2020 the government plans to begin construction in 2021.

But today 100 per cent of the mine’s electricity needs are met by China. This comes at a price of approximately $100 million annually.

Energy subsidies are killing infrastructure

Orchlon is frustrated by the government ignoring energy infrastructure needs until they reach a crisis point. ‘It’s the same situation for heating in UB, actually,’ he says, explaining the city’s urgent infrastructure needs in coming years.

According to Orchlon, ‘The energy sector is so behind because we don’t consider electricity to be a product. We think it’s a social benefit that we’re entitled to and that it’s the government’s duty to provide.’

At a mere $0.04 per kilowatt hour, Mongolia’s electricity costs are some of the lowest in the world because it is heavily subsidized across the supply chain.

As a point of comparison, Orchlon points out that the average Mongolian household pays only $7.50 to $9.50 for their monthly electricity bill but will pay $15 for a bottle of vodka. He says that if you visit the APU spirit company, which produces the award-winning Chinggis Khan brand of vodka, their facility is state-of-the- art because they are able to take their profits and reinvest them into their business. In comparison, Mongolia’s energy infrastructure is crumbling. The power plants and transmission lines are outdated and insufficient to handle the country’s energy needs.

Mongolia has untapped energy potential...

‘We do have a lot of coal, but we do have a lot more wind and solar,’ says Orchlon. For Orchlon, using Mongolia’s renewable energy sources isn’t just an abstract thought. As the CEO of Clean Energy Asia, Orchlon is working towards securing Mongolia’s place in a new energy future.

While otherwise problematic, Mongolia’s dry climate means that the sun is nearly always shining in the land of eternal blue sky. Those rays can be collected by solar panels and converted to electricity. The frequent desert winds that cause pesky dust storms can be captured by wind turbines and used for power. ‘In terms of potential, we actually have enough wind and solar resources to power the whole of Asia,’ says Orchlon.

… that could power all of Asia

SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son and his colleagues are working towards the Asia Super Grid concept involving building a cross-border power grid system connecting China, South Korea, Mongolia, Russia, and Japan. Its estimated cost is $6.2 billion.

In its final phase, the grid will reach as far as southeast Asia and India. Mongolia is at the heart of their plan—giant wind farms will feed renewable energy into the grid, generating export earnings for the country. Orchlon’s role in the project is to make sure that the renewable energy infrastructure in Mongolia gets built.

In 2017, after $128 million in investment, Clean Energy Asia opened the Tetsii windfarm, a 50-megawatt operation in the Gobi Desert. The project broke records for being the fastest-built farm of its size while also coming in under budget.

Orchlon credits the combination of Mongolian and Japanese strengths to the project’s success—‘Mongolians are very “roll up our sleeves, get it done,”’ he says. ‘And the Japanese are very focused on planning.’ While the Tetsii wind farm currently only supplies Mongolia, investors see its success as an indication that the Asia Super Grid project is truly feasible.

Building the wind farm meant getting permission from local herders, who have become more cautious about large projects being built on their land after seeing the destruction wrought by mining development.

A rumour had spread among herders that the turbines would blow away the clouds, making it rain less and drying out their lands. They also worried that the area would be fenced off, preventing them from grazing their animals.

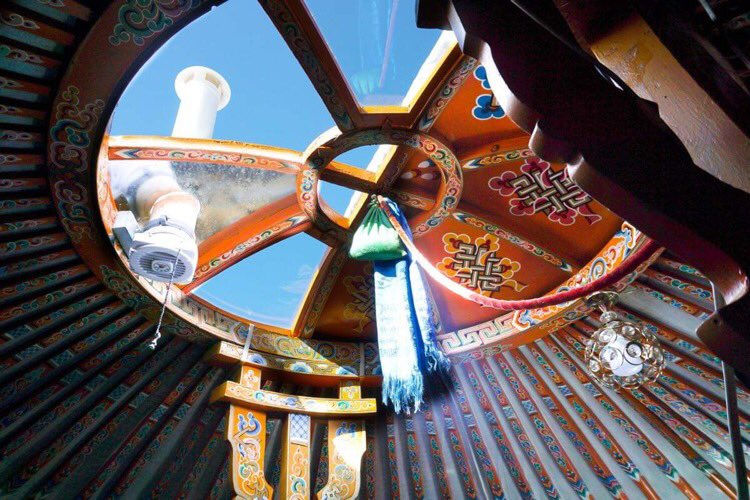

To secure the buy-in of herders, Orchlon went on what he describes as a campaign: he donned his finest deel and went ger to ger addressing misconceptions and concerns.

He explained that the lowest clouds form at 3,000 metres and that wind turbines are 90 metres tall; wind turbines don’t generate wind bursts like fans do, but rather use the energy, like pinwheels. Area residents are now happy about the role their region plays in supplying clean energy and Orchlon describes getting the enthusiastic support of the community as his proudest accomplishment.

The future is clean

Currently, about 6 percent of Mongolia’s energy needs are met by renewable sources and the fragility of Mongolia’s grid will make it difficult to add much more intermittent renewable energy. Because solar and wind energy vary depending on the weather and time of day, they are a less stable energy source than traditional power generation methods. They cannot be turned on and off, meaning that they cannot adjust to meet the needs of the power grid.

The solution is for solar and wind farms to add storage capacity so that power can be banked and added to the grid more smoothly, with batteries being used to absorb fluctuations. Unfortunately, storage technology is still prohibitively expensive, but Orchlon is optimistic that the price will drop quickly as the renewable energy marketplace expands.

The Tetsii windfarm was built along the Gashuun Sukhait Road in the Gobi Desert, the same road that is used to truck coal from the Tavan Tolgoi mine into China. Sheep that graze there have had their coats turn black from coal dust and the exhaust of trucks that idle in long lines to bring the coal across the border. But on the other side of the road, white wind turbines reach towards the sky, promising a cleaner future.

Unlike the fraught discovery of mineral deposits, generating renewable energy may give Mongolia an opportunity to not only develop itself, but to develop the world in a sustainable way.

Aubrey Menard is an author of "Young Mongols: Forging Democracy in the Wild Wild East” book and a highly sought-after expert on politics, elections, and democracy. She’s been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Al Jazeera, Politico, and the South China Morning Post. She lived in Mongolia and worked on democracy and governance issues in Asia and other parts of the world.

This article originally appeared in our weekend newsletter, along with a whole lot more. Give it a try for free and access unrivalled coverage and analysis of Mongolian politics, economics and current affairs from our specialist journalists and contributors based in Ulaanbaatar and across the globe.

Simply follow this link to subscribe.

Comments